Understanding the Problem: Translation Isn’t Enough

In global research, translation is often mistaken for localization. Many researchers assume that once a questionnaire or scale is linguistically translated, it becomes universally applicable.

However, translation alone rarely guarantees conceptual equivalence—the idea that a question measures the same construct in another language or culture.

For example, a “satisfaction survey” developed in the U.S. might not resonate the same way in Bangladesh or Japan because cultural expressions, emotional norms, and response patterns differ drastically. The result? Data that appears comparable but lacks cross-cultural validity.

Translation vs. Localization: What’s the Difference?

Translation is the process of converting words from one language to another.

Localization, however, is adapting the content to ensure it makes cultural, contextual, and conceptual sense to the target audience.

In research instruments, localization ensures that:

- Questions maintain the same meaning, not just similar words.

- Cultural norms and idioms are contextually relevant.

- Scales and measurement units are interpreted equivalently.

- Emotional tone and response options fit local norms.

Localization, therefore, bridges the semantic gap between languages to protect the validity and reliability of your data.

Why Most Translated Instruments Fail

Despite its importance, localization is often ignored in academic and applied research. The reasons include:

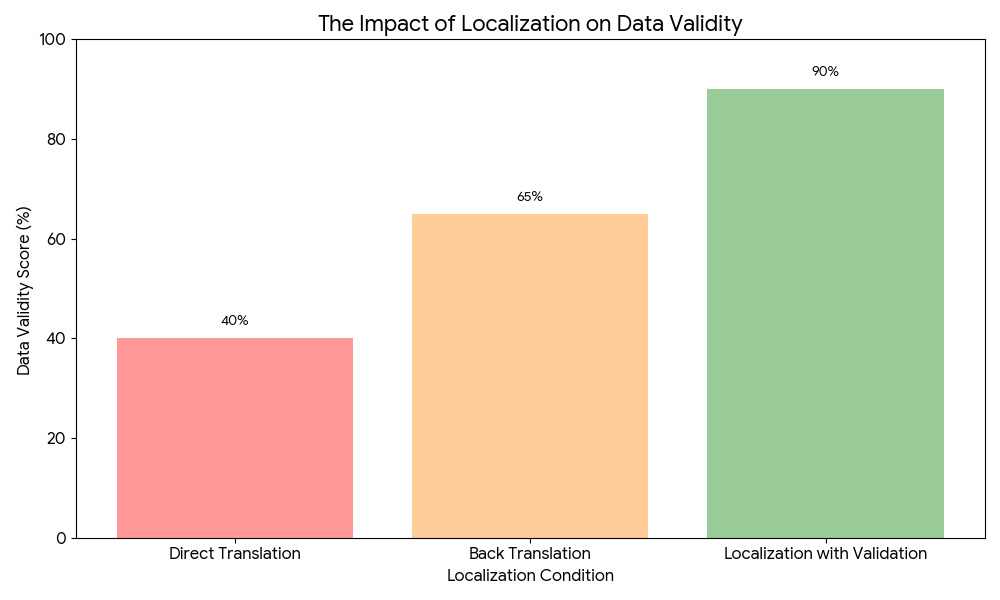

Overreliance on Direct Translation

Researchers often use literal or back translation (forward–backward method) assuming it’s enough.

While this method helps catch linguistic errors, it cannot capture cultural or conceptual mismatches—for example, how “privacy” or “mental health” are perceived differently across societies.

Ignoring Cultural Context

Culture shapes how people understand, interpret, and respond to questions.

A Likert scale item like “I express my feelings openly” may indicate openness in the U.S. but could signify improper behavior in cultures that value restraint.

Lack of Pretesting and Validation

Few researchers pilot their translated instruments across different cultural samples.

Without cognitive interviewing, focus groups, or expert reviews, subtle meaning distortions go unnoticed—leading to invalid comparisons.

Missing Semantic, Conceptual, and Technical Equivalence

A valid cross-cultural instrument must ensure equivalence at three levels:

| Type of Equivalence | Definition | Example |

| Semantic | Words convey the same meaning | “Family” may differ between nuclear vs. extended family cultures |

| Conceptual | Constructs are understood the same way | “Independence” may mean autonomy in one culture, rebellion in another |

| Technical | Measurement scales function similarly | 5-point scales may not behave identically across cultures |

Without ensuring these, translation becomes a superficial exercise.

How Localization Enhances Research Validity

Localization is not merely rewriting—it’s re-contextualizing research tools. It involves:

- Engaging bilingual experts and cultural specialists.

- Conducting pilot tests in multiple cultural settings.

- Using parallel translation and committee review methods.

- Applying statistical validation techniques, such as factor analysis or measurement invariance testing.

These steps ensure the instrument measures the same psychological construct across cultures, not just the same text.

Case in Point: The WHO Example

The World Health Organization (WHO) never relies on translation alone for health surveys like the WHOQOL (Quality of Life Instrument).

They follow a systematic localization protocol—including cultural adaptation, pilot testing, and cross-validation—to maintain conceptual equivalence across 30+ languages.

This process is why WHO instruments remain globally valid and comparable (source: WHOQOL User Manual).

The Research & Report Consulting Advantage

At Research & Report Consulting, we specialize in cross-cultural instrument localization.

Our experts ensure your tools maintain both linguistic precision and conceptual accuracy through advanced validation protocols.

We don’t just translate—we preserve meaning, ensuring your findings are credible, comparable, and globally defensible.

We strengthen the validity of your research instruments through professional localization and cross-cultural validation.

References

- Brislin, R.W. (1970). Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology.

- van de Vijver, F.J.R., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research. Sage Publications.

- World Health Organization. (2004). WHOQOL User Manual. WHO Website

- Beaton, D.E., et al. (2000). Guidelines for Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine Journal.

- Harkness, J. (2003). Cross-Cultural Survey Methods. Wiley.

Final Thoughts

Translation helps you reach new audiences.

Localization ensures you understand them.

Without localization, translated instruments lose their scientific validity and cultural sensitivity—making your data unreliable and your insights misleading.

At Research & Report Consulting, we bridge this gap with evidence-based localization strategies that protect your research from cross-cultural distortion.

Have you ever tested your translated instruments for conceptual equivalence? Share your experience below — your insights could guide others.

Want research service from Research & Report experts? Please contact us.