Many researchers assume that once they receive an institutional review-board (IRB) or ethics committee approval, their ethical obligations are fully met. This assumption is risky and can lead to major integrity gaps in research. Ethical clearance is not a full guarantee of ethical conduct: it is only the starting line. The real ethical work takes place beyond the form — during data collection, participant interaction, and dissemination.

The Misconception of One-Time Approval

When a research project obtains an approval letter, many researchers check the box and move on. But an ethics approval letter only confirms that the proposed plan as submitted meets institutional criteria at one point in time.

- It does not account for dynamic field conditions.

- It does not automatically ensure ongoing protections for participants.

- It does not make the researcher immune from ethical decision-making later.

As one study notes: “many researchers and/or institutions only focus on ethics linked to the procedural aspects.” Emerald insight

Four Critical Issues Researchers Often Overlook

1. Ongoing Consent Matters More Than Initial Consent

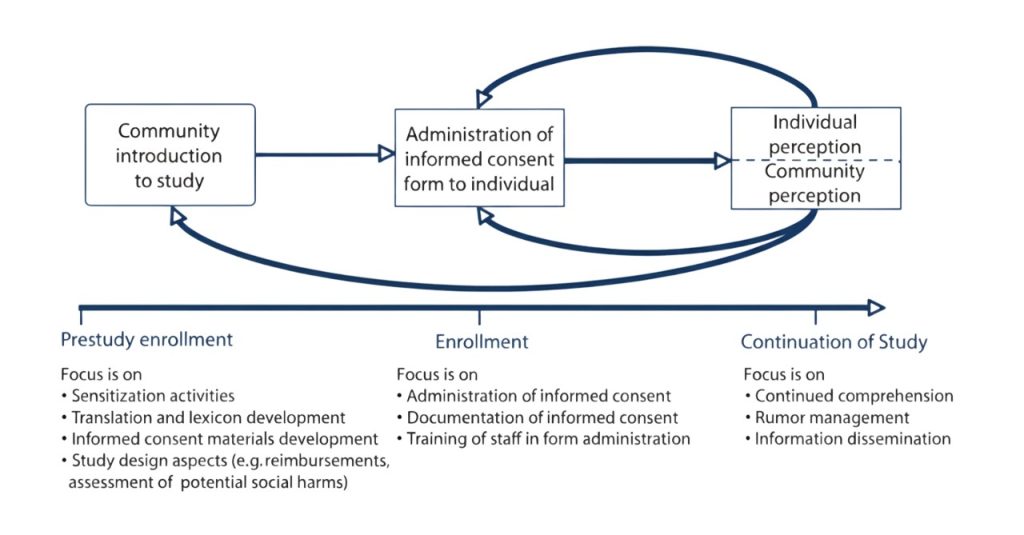

Informed consent typically happens at the start of a study. But participants may change their minds, feel pressure, or misunderstand the risks. Ethical research requires clear, voluntary, and ongoing consent throughout the research lifecycle.

According to research on participant consent: “The ethical issues … respect for free, informed and ongoing consent of research participants.” PMC

For example, in digital or remote research, participants may click “I agree” but not really understand. A recent paper found that online consent forms often lead to “uninformed decisions.” arXiv

Therefore: ensure consent forms are clear, and check‐in with participants at key phases of the study.

2. Vulnerability Is Dynamic, Not Static

Researchers often treat certain populations as “vulnerable” and apply blanket protections. But vulnerability changes with context: crisis, gender norms, local politics, or shifting power relations.

For example, the Havasupai Tribe v. Arizona Board of Regents case showed that indigenous participants were not fully protected because researchers reused DNA samples beyond the original intent—resulting in a breakdown of trust. Wikipedia

Guidance states that “vulnerability may vary over time; people may be considered vulnerable at some stages but not in others.” neac.health.govt.nz

Researchers must monitor how context and participant circumstances evolve, and adjust protections accordingly.

3. Researcher Positionality Shapes Power Relations

The identity, authority, socio‐economic status, and affiliations of the researcher shape how participants respond. Ignoring this positionality means ignoring how power imbalances play out.

Studies on qualitative research emphasise reflexivity and positionality as central: “researcher positionality in relation to the ethical and emotional work involved in research” ResearchGate

For example, a researcher from a privileged institution interviewing marginalized populations may inadvertently influence answers or create coercion. Recognizing your own positionality, reflecting upon it, and building safeguards is essential.

4. Field Realities Can Break Protocols

Ethics review forms assume controlled, ideal conditions. In reality: participants may feel fear, be influenced by gatekeepers, face sudden risks, or the context may shift. Ethical research requires responsive judgement, not rigid form‐filling.

An ethics governance article states: “Researchers should proactively consider the ethical implications before, during and after the actual research process.”

In other words: ethics is a process, not a document.

Practical Steps for Ethics-Aware Research

- Build consent check-ins: Plan periodic reminders or confirmations that participants still wish to participate and understand the process.

- Design for vulnerability: Conduct risk assessments that look for shifting vulnerabilities (e.g., changed employment, local conflict, health crises).

- Reflect on your positionality: Include reflexivity journals, team debriefs and participant feedback to surface power dynamics.

- Create protocols for adaptation: Build frameworks for how to respond when field conditions change (e.g., withdraw participants, pause research, redesign questions).

- Embed ethical culture in your team: Ethical research must be a continuous mindset, not only when applying for approval.

Why Your Research Firm Should Lead This Shift

At Research & Report Consulting, we believe that ethical research is not just about compliance: it’s about trust, integrity and rigorous methodology.

➡️ We design ethics-aware research processes — not just forms.

Your reputation, the validity of your data, and the dignity of participants depend on this approach.

Conclusion

An approval letter is necessary—but it is rarely sufficient. Ethical research demands ongoing consent, attention to dynamic vulnerability, critical reflection on researcher positionality and a process orientation.

We design ethics-aware research processes—not just forms.

Want to upgrade your research ethics framework? Contact us to build deeper, more responsible research protocols.

💬 What challenge have you faced in applying ethics beyond the approval stage? Share your experience below.

References

- Biros M. “Capacity, Vulnerability, and Informed Consent for Research.” PMC. 2018. PMC

- Venäläinen S. “Am I vulnerable? Researcher positionality and affect in qualitative research.” SAGE. 2023. SAGE Journals

- Nii Laryeafio M. “Ethical consideration dilemma: systematic review of ethics in qualitative research.” Emerald. 2023. Emerald

- “Ethical management of vulnerability.” National Ethics Advisory Committee (New Zealand). 2023. neac.health.govt.nz

- “Ethical considerations in qualitative research” – ATLAS.ti guide. 2023. ATLAS.ti

- “Ethics and positionality in qualitative research with vulnerable and marginal groups.” ResearchGate. ResearchGate

- “Ethical issues in research: perceptions of researchers, research ethics board members and research ethics experts.” PMC. 2022. PMC

- “Declaration of Helsinki.” Wikipedia. 2024. Wikipedia